…

TRACING THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE PRC THROUGH THE LEI FENG CAMPAIGN

Abstract

Lei FENG was a Chinese soldier whose diary earned him posthumous fame as it showed Lei’s selfless actions and loyalty to Mao ZEDONG and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Interestingly, certain elements of the “Learn from Lei FENG” Campaign kept changing after his passing. This paper is written to point at the parallels between these changes and the transformation of the CCP’s understanding of governance.

Introduction

Lei FENG (雷锋) (1940-1962) probably is the most famous People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldier ever. After his death, his diary, which was filled with his writings showing his fidelity for Mao ZEDONG, the CCP, the motherland and the people was used for propaganda purposes in the mid-1960’s. As a person who continuously worked for the people, Lei FENG was presented as a model citizen (Sullivan, 2007).

Lei FENG became an important part of the contemporary Chinese culture. Songs and movies were made about him, March 5 is declared as “Learn from Lei FENG Day” and in 2005, a video game called “Learn from Lei FENG Online” was released (china.org.cn, 2006). Chinese leaders after Mao praised his acts as well. Deng XIAOPING used Lei FENG as an example for army discipline on December 28, 1977, (Deng, 1995). Hua GUOFENG called the authorities to launch a “Learn from Lei FENG” campaign in his speech on March 14, 1977, (Hua, 1977). Current Chinese President Xi JINPING emphasized the need to carry the Lei FENG spirit for the later generations (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2018).

An interesting point about Lei FENG is that the portrayal of him to the public changes as the concerns of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) administration shifts. Major Lei FENG Campaigns were done many times in many years, between 1963 and 2013 with each campaign having a different understanding of Lei FENG (Jeffreys & Su, 2016). This paper’s argument is that these different focuses show the transformation of the PRC and the CCP’s administration.

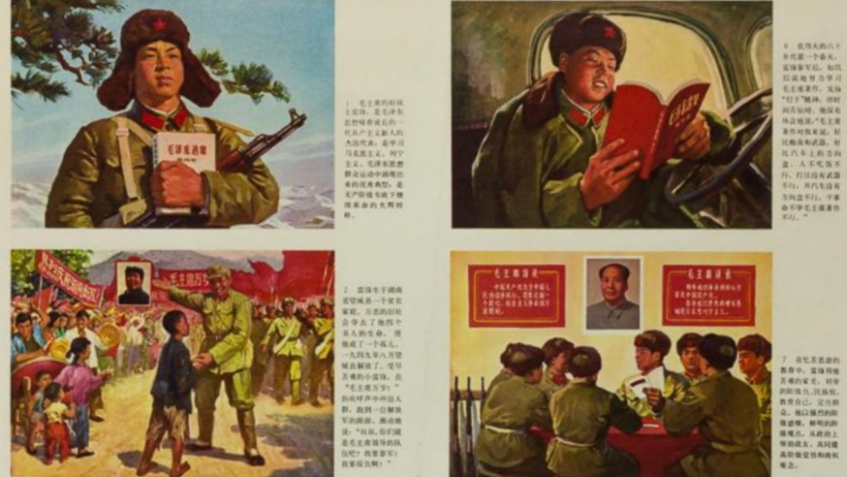

Lei FENG Campaign During the Cultural Revolution

After the original Learn from Lei FENG Campaign of 1963, another major Learn from Lei FENG Campaign was launched in 1966, in the days of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) (Jeffreys & Su, 2016). Study groups were set up for the people of all ages, especially teenagers, to study Lei FENG at all times. During the Cultural Revolution, Lei FENG’s great loyalty to Mao ZEDONG was stressed (Dugue, 2009). Certain parts were added to Lei FENG’s diary which showed how Lei FENG “fought against class enemies”. For example, in an addition made in 1968, Lei FENG is inspired by Mao ZEDONG’s writings and denounces the local Worker’s Union chairman for his upper-class family background (Tian, 2011). Cultural Revolution was an era in which more radical elements loyal to Mao and his deputy Lin BIAO purged the moderates led by Liu SHAOQI. As the leading clique got more radical, so did the characteristics of the Revolution. Intellectuals and those of upper-class descent were targeted as “capitalists” (Sullivan, 2007). In this campaign, the focus on Lei FENG’s loyalty to Mao shadows his other attributes, such as his love for the people. Combined with the additions to the diary about Lei FENG “fighting against the class enemies”, these shifts totally reflect the spirit of the Cultural Revolution.

Lei FENG in the Post-Mao Era

Following the Cultural Revolution and the death of Mao, Lei FENG’s image was changed again. Unlike the Lei FENG of the Cultural Revolution, whose human side was taken away and was presented as a loyal machine, this new Lei FENG was regranted these attributes. After a brief period of Hua GUOFENG’s administration, Deng XIAOPING took over and conducted the widespread reforms he is known for today. Under Deng, Lei FENG was used to publicize a new set of values, named “socialist spiritual civilization” by Deng himself (Jeffreys & Su, 2016). New posters of Lei FENG published in this period associated Lei FENG with technological progress, prosperity, entrepreneurship, and modernity (Dugue, 2009). Lei’s diary went through another change in the period, with the Cultural Revolution’s additions getting removed and the parts about Lei’s human desires getting readded (Tian, 2011). Deng XIAOPING’s era marks an enormous shift in the PRC’s policies, with the political elite abandoning Mao’s rapid revolution ideals and recognizing the bourgeoise’s contributions to progress and development, named “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” (Sullivan, 2007). Portrayal of Lei FENG in this period corresponds to the CCP becoming more tolerant towards all classes and the economic make-up of the country changing dramatically.

Maybe the biggest revival of the Lei FENG Campaign happened in 1989. After the Tiananmen Square events, to motivate the troops and boost devotion to the CCP, another Lei FENG Campaign was launched (Slate, 2003). The General Political Department of the PLA took several steps, such as publishing 300.000 copies of Lei FENG’s diary and giving these away to soldiers and requesting all soldiers to read it and to think about Lei FENG’s deeds (Shambaugh, 1991). Party organs started to call on government officials to start a new campaign to introduce the new generation to Lei FENG with the aim of achieving “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” (Jeffreys & Su, 2016). In the period when the Chinese administration had to deal with pro-democracy protests inside and the sudden disintegration of the Eastern Bloc outside, Lei FENG was used as a sign of dedication to the CCP’s line and its goals as the party had to present a model for people to unite behind in a time of struggle.

In 2008, a spontaneous movement of volunteerism rose in China when the Great Sichuan Earthquake of 2008 happened with millions of people volunteering to help those in need directly or indirectly. In the same year, a million people volunteered to serve in the Beijing Olympics. While these two events showed the sense of unity Chinese people had, the Chinese government wanted to make sure that volunteering activities would not turn into those like the movements of 1989, a threat to the existence of the CCP. Thus, another Lei FENG Campaign began in 2012, combining Lei FENG and volunteerism together and teaching volunteers to stay “patriotic”, as in “loyal”, just like Lei FENG (Palmer & Ning, 2020). Lei FENG was used for non-political reasons this time. He became the face of a moral campaign for civil cooperation and mutualization as the conditions of the time dictated so.

Conclusion

It is seen that the nature of the Lei FENG Campaign changed its nature over time. While all “Learn from Lei FENG” campaigns were centered around the same Lei FENG who died years ago, each of them focused on different sides of him, accordingly with the demands of the era.

During the chaotic days of the Cultural Revolution, Lei FENG was presented as a machine whose only characteristic was his loyalty for Mao to instill the radical ideas of the period to the people. When the Cultural Revolution ended, Lei FENG was portrayed as a more “human” figure, with emotions and desires, and became the symbol of the entrepreneurship promoted by the CCP elite of the time. When the Tiananmen Square Incident of 1989 happened, the CCP used Lei FENG’s loyalty to boost unity and loyalty to the regime in the country. When the country was going through huge events of the Great Sichuan Earthquake and the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Lei FENG’s habit of altruistically helping others was used to incite waves of volunteerism.

In conclusion, just like how Lei FENG described himself as a “rust-proof screw in a huge machine” in his diary (People’s Daily, 2022), the campaign named after him was used for all major events the country faced after his death with greater purposes. Tracing the evolution of the campaign gives clues for the governance philosophy of the CCP elite of the eras since the 1960’s.

References

china.org.cn. (2006, March 15). Lei FENG Becomes Online Game Hero. Retrieved from China Internet Information Center: http://www.china.org.cn/english/Life/161833.htm

Deng, X. (1995). Speech at a Plenary Meeting of the Military Commission of the Central Committee of the CPC. Selected Works of Deng XIAOPING: Volume II (s. 94). Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Dugue, C. A. (2009). Lei FENG: China’s Evolving Cultural Icon, 1960s to the Present. University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations.

Hua, G. (1977, March 14). March 14, 1977: Hua GuoFENG’s Speech at the Central Work Conference. Wilson Center Digital Archive: Retrieved from http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121681

Jeffreys, E., & Su, X. (2016). Governing through Lei FENG: A Mao-era Role Model in Reform-era. New Mentalities of Government in China, 30-55.

Palmer, D. A., & Ning, R. (2020). The Resurrection of Lei FENG: Rebuilding the Chinese Party-State’s Infrastructure of Volunteer Mobilization. E. Perry, G. Eckiert, & X. Yan içinde, Ruling by Other Means: State-Mobilized Social Movements. Cambridge University Press.

People’s Daily. (2022, March 6). Xi Story: A screw that never rusts. Retrieved from People’s Daily Online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2022/0306/c90000-9966818.html

Shambaugh, D. (1991). The Soldier and the State in China: The Political Work System in the People’s Liberation Army. The China Quarterly, 527-568.

Slate, R. (2003). Chinese Role Models and Classical Military Philosophy in Dealing with Soldier Corruption and Moral Degeneration. Journal of Third World Studies, 193-224.

Sullivan, L. R. (2007). Cultural Revolution. Historical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China (s. 143). Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

Sullivan, L. R. (2007). Historical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

Sullivan, L. R. (2007). Lei FENG. Historical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China (s. 314). Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

Sullivan, L. R. (2007). Socialism. Historical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China (s. 457). Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2018, September 29). Xi stresses revitalization of Northeast China. Retrieved from Website of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China: http://english.www.gov.cn/news/top_news/2018/09/29/content_281476323331411.htm

Tian, X. (2011). The Making of a Hero: Lei FENG and Some Issues of Historiography. The People’s Republic of China at 60, 291-305.

- MİKROÇİPLER, TAYVAN VE TEKNOLOJİK KIYAMET - 8 Ekim 2022

- TRACING THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE PRC THROUGH THE LEI FENG CAMPAIGN - 1 Temmuz 2022

- ORTA ASYA’DA HİNDİSTAN: ÇIKARLARI VE SORUNLARI - 4 Nisan 2022

- G7 LİDERLERİNİN RUSYA FEDERASYONU SİLAHLI KUVVETLERİNİN UKRAYNA’YI İŞGAL ETMESİ HAKKINDAKİ BİLDİRİSİ - 25 Şubat 2022

- ÖZGÜRLÜK ANANASLARI VE TAYVAN’IN JEOPOLİTİK ÖNEMİ - 23 Kasım 2021

- HİNT OKYANUSU’NDA ÇİN: İNCİ DİZİSİ KURAMI - 17 Eylül 2021