…

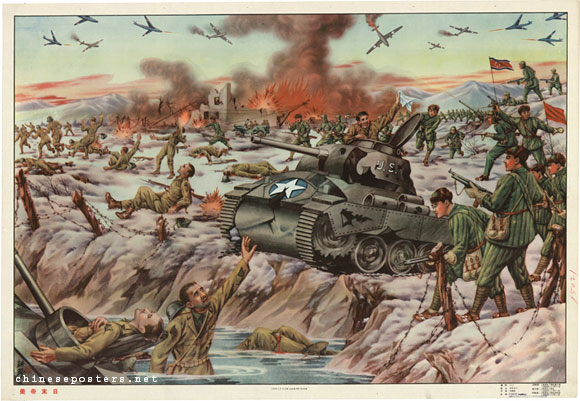

CHINESE INTERVENTION IN THE KOREAN WAR

Zeynep Ceren ERTÜRK

Section 1: Introduction

The Korean War was one of the highlights of the post-World War II era and the Cold War era. In fact, when the Korean War is mentioned, not only the separation of North and South Korea and the fact that a country as isolated as North Korea remains in the new world order, but also many reasons and consequences are discussed. The war can be considered as a war between the United States and Soviet Russia, or between the United States and China, as well as between North and South Korea. However, in this paper, although there are many topics that can be clarified and interpreted regarding the Korean War, the main point to be examined is the reasons for China’s intervention in the Korean War. In the west, it has long been assumed that the Chinese were motivated by a mix of xenophobic sentiments, security threats, expansionist impulses, and communist doctrine.[1] The increasing Cold War impacted Western researchers in the 1950s, who claimed that China’s engagement into the Korean War was mostly due to Stalin’s directive to promote communism.[2] Allen S. WHITING suggested in 1960 that the time when China felt the full border security threat and needed a military intervention was after the successful landing of American General MacArthur on Incheon on September 15, 1950.[3] Nevertheless, Chinese scholars began to argue in the 1980s that the United States’ rapid involvement in the Korean War, as well as Truman’s public release of the deployment of the 7th Fleet to the Taiwan Strait, validated to Mao that the United States was seeking militarized aggression against Chinese territorial sovereignty.[4] Recently, a Chinese scholar argued that Mao continued sending troops upon Soviet’s encouragement to do so, due to the fact that he sought to obtain security assurance and economic assistance from the Soviet Union.[5]

With respect to abovementioned arguments, the research question of this paper to be shed light on is “Which events, actions, or motivations triggered the People’s Republic of China’s intervention in the Korean War?”. However, this paper argues that the main period and events which triggered MAO Zedong to change his timid and concerned stance towards the idea of direct intervention in the war were the UN forces landing at Incheon under MacArthur’s command on September 1950, and Truman signing a declaration granting UN troops permission for crossing the 38th parallel. In short, the claim is that the primary motivation of the People’s Republic of China, or rather MAO Zedong, to intervene in the Korean War on 19 October 1950 was to eliminate the security concerns.

Section 2: The Communist Chinese Party and China’s Relations with the US in the Newly Established People’s Republic of China

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has faced strong resistance from practically every Western country since its inception.[6] Despite the unfriendly approach and Roosevelt’s policy of supporting CCP’S rival Guomindang, the CCP strove to develop a neutral relationship with the US. However, because the Truman administration continued to back Guomindang, CCP leaders opted to form an alliance with the Soviet Union between 1946 and 1949 and seek for economic and military assistance.[7] Mao emphasized the immediate recovery and reconstruction of the economy between 1947 and 1949, prior to the formation of the People’s Republic of China, to have the capability to withstand a probable US blockade.[8] Certainly, the United States was not the sole source of concern. First and foremost, China needed to heal its scars from ages of successive battles. Second, the PRC was newly established and had an unstable economy. Third, land reform in newly freed areas and democratic reform in cities have yet to be implemented. Fourth, anti-revolutionaries and rebels remained a source of anxiety. Finally, China was military-wise weak in comparison to the West and the Soviets as it lacked air and naval command.[9] Therefore, the common opinion among CCP leaders was to avoid direct confrontation with the U.S. and the West in general. Expectedly, the transfer of the 7th Fleet to the Taiwan Strait on 27 June 1950[10] rattled the newly founded CCP regime’s political and economic foundations, proving Mao and his associates right to be concerned about US hegemony.

Section 3: Chinese Foreign Relations with the USSR and North Korea in the Pre-Korean War Period

Following the Second World War, national security became the fundamental strategic goal of Soviet foreign policy. Moderate coexistence and communist revolution came second. Nonetheless, Stalin’s worries and strategic ambitions changed as a result of the Marshall Plan of June 1947. The Soviets’ position towards the US became increasingly hostile as he interpreted the Marshall Plan to form an anti-Soviet bloc in Europe.[11] The newly established People’s Republic of China has already been seeking for an ally, from which she could get economic and military assistance for countering external and internal threats. Stalin, on the other hand, was hesitant to embrace a full-fledged strategic partnership with the People’s Republic of China as it had the potential to become an enemy in the East, even though the CCP expanded the Soviet Union’s safety zone and helped promote Communist influence in the region.[12] Eventually as the U.S. threat seemed more in presence between 1947-1950, the PRC and USSR, still holding to their strategic concerns, signed the Sino-Soviet Alliance, Friendship, and Mutual Assistance Treaty in February 1950. Despite the fact that this deal did not match Mao’s expectations for the future, it did technically assure to provide China with unconditional Soviet assistance and backing in the event that it was occupied.[13]

Prior to the Korean War, the CCP leaders had turned a blind eye to the Korean Peninsula and had limited knowledge of the situation in North Korea, not to mention lacking practice of diplomacy. In fact, it wasn’t until late August 1950 that the Chinese Embassy in Pyongyang was opened.[14] Yet, starting from the beginning of the war, Kim Il-Sung started to ask for both Chinese and Soviet support. However, once the war broke out, CCP leaders at utmost gave moral support to North Korea and initiated to send 14,000 Korean Chinese as manpower support.[15] As concerned as Mao and CCP government were concerned, initially they were reluctant to pave the way for a highly risky confrontation with imperialist West, specifically the United States.

Section 4: The Early Period of the Korean War Leading to Chinese Intervention

Prior to the outbreak of the Korean War, neither Stalin, Mao, nor KIM Il-Sung anticipated that the US would intervene in the dispute.[16] In fact, when Mao and Kim Il met in early May 1949, they discussed a probable intervention of the Japanese troops.[17] The Truman administration, nonetheless, issued a resolution at the United Nations on June 27, 1950, two days after the war erupted, calling on all nations to aid South Korea and enabling US naval and air troops to defend South Korea.[18] The deployment of the 7th Fleet to the Taiwan Strait on July 7, 1950, however, was the final straw for the Chinese, who saw it as an intrusion into the PRC’s domestic affairs, as this paper claimed previously. General MacArthur was designated commander of UN forces—primarily US forces—under the Security Council Resolution of July 7, signaling the start of a complete intervention in the Korean War. China reaffirmed its stance on intervention following the introduction of US ground troops in Korea. On July 2, 1950, Zhou Enlai, the PRC’s Premier and Foreign Minister, notified Stalin that “if the Americans cross the 38th parallel, Chinese troops dressed as Koreans will use volunteers to take combat against them.”[19] Stalin agreed on July 5 to the Chinese demand for air support, stating that “we will do our best to provide air cover for these units.”[20] North Korean forces invaded the entire Korean Peninsula in early August1950, with the exception of the south eastern edge of Busan, which remained under UN authority.[21] Seoul was recaptured by the UN troops on September 28, 1950, and Truman signed a treaty permitting UN soldiers to pass the 38th parallel.[22] The time for Stalin to encourage Mao for entering the war had come as the US threat was more evident then ever. On October 5, Stalin sent Mao a message claiming that if China joined the war, the United States would be compelled to leave Taiwan, hence encouraging China to send troops to the Korean Peninsula. In addition, Stalin reassured Mao by stressing that the Soviet Union would fight alongside China under the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Alliance, Friendship, and Mutual Assistance signed in February 1950.[23] Stalin’s encouragement was indeed pressure, signing the worsening of relations between China and the USSR if China had disagreed. On October 11, 1950, Minister ZHOU Enlai met Stalin to discuss the ultimate situation and request assistance and material support to enter the Korean lands. However, Stalin was not willing to compromise and provide Soviet air force, thus stated that the assistance would not be at such level.[24] The joint telegram Stalin and Minister Zhou Enlai sent to Mao, dated October 11, 1950, clearly stated that China would not have the expected assistance, military equipment, and air force support that it lacked (Appendix 1). Mao, who gathered the leaders of the CCP and opened the telegram to discussion, although he was worried at first, insisted to intervene in the war and had done so on October 19, 1950.[25]

Section 5: Conclusion: The Rationale Behind Chinese Intervention in the Korean War

Initially, the People’s Republic of China deeply wished for North Korean success for the promotion of communist revolution and to guarantee the sustainability of newly established CCP regime. Mao highlighted that the Chinese objective was to promote the revolution while supporting its spread in the Korean peninsula. However, the need to promote revolution was, again, to guarantee the security and sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China and the protection of “Chinese Revolution” first.[26] The impetus for intervening in the war in the name of internal affairs and strengthening the regime’s reputation was to increase internal morale and to prove to be superior to the Guomindang, which had the advantage of receiving assistance from the United States.[27] However, the level of threat perceived by the Chinese Communist Party, especially once the 7th Fleet was dispatched to the Taiwan Strait at the very beginning of the war, increased significantly. This paper concludes with the claim that among several reasons, the prominent reason for the Chinese intervention in the Korean War was the CCP’s perception that the US presence was posing a threat to the Chinese borders, integrity and sovereignty; a claim that was eventually justified by MacArthur led UN forces’ actions and the defeat of the Chinese Communists.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Allen S. Whiting, China Crosses the Yalu: The Decision to Enter the Korean War (New York, 1960), 126, 159-60.

- David, T. C. (2015). China’s military intervention in Korea: Its origins and Objectives. Trafford Publishing.

- Donggil Kim, China’s Intervention in the Korean War Revisited, Diplomatic History, Volume 40, Issue 5, November 2016, Pages 1002–1026.

- Mosley, E. Philip “Soviet Policy and the War,” Journal of International Affairs 6 (Spring 1952): 107-14.

- Kovach, C. (2016). “What Were Mao’s Motivations for Intervention in the Korean War?” Interstate – Journal of International Affairs, 2015/2016(3).

- Shen, Zhihua. “China and the Dispatch of the Soviet Air Force: The Formation of the Chinese–Soviet–Korean Alliance in the Early Stage of the Korean War.” Journal of Strategic Studies 33, no. 2 (2010): 211–30.

- Shen, Zhihua. “Sino-Soviet Relations and the Origins of the Korean War: Stalin’s Strategic Goals in the Far East.” Journal of Cold War Studies 2, no. 2 (2000): 44–68.

- “The Korean War and the Fate of Taiwan.” Taipei Times, June 29, 2010.

- Torkunov, Anatoly. The War in Korea 1950-1953: Its Origin, Bloodshed and Conclusion (Tokyo, 2000), 50-51.

- Yufan, Hao, and Zhai Zhihai. “China’s Decision to Enter the Korean War: History Revisted.” The China Quarterly 121 (1990): 94–115.

- Zhou, B. (2015). “Explaining China’s Intervention in the Korean War in 1950.” Interstate – Journal of International Affairs, 2014/2015(1).

Appendix 1: Stalin-Zhou Enlai Joint Telegram to Mao Zedong, October 11, 1950

[1] Hao Yufan and Zhai Zhihai, “China’s Decision to Enter the Korean War: History Revisted,” The China Quarterly 121 (1990): pp. 94-115, 94.

[2] Philip E. Mosley, “Soviet Policy and the War,” Journal of International Affairs 6 (Spring 1952): 107-14.

[3] Allen S. Whiting, China Crosses the Yalu: The Decision to Enter the Korean War (New York, 1960), 126, 159-60.

[4] Donggil Kim, “China’s Intervention in the Korean War Revisited,” Diplomatic History 40, no. 5 (2015): pp. 1002-1026, 1003.

[5] Zhihua Shen, “China and the Dispatch of the Soviet Air Force: The Formation of the Chinese–Soviet–Korean Alliance in the Early Stage of the Korean War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 33, no. 2 (2010): pp. 211-230.

[6] Yufan and Zhihai, 95.

[7] Yufan and Zhihai, 95.

[8] Yufan and Zhihai, 99.

[9] Kim, 1015.

[10] “The Korean War and the Fate of Taiwan.” Taipei Times, June 29, 2010.

[11] Zhihua, Shen. “Sino-Soviet Relations and the Origins of the Korean War: Stalin’s Strategic Goals in the Far East.” Journal of Cold War Studies 2, no. 2 (2000): 44–68, 46-47.

[12] Zhihua, 2000, 54.

[13] Zhou, B. (2015). “Explaining China’s Intervention in the Korean War in 1950.” Interstate – Journal of International Affairs, 2014/2015(1).

[14] Yufan and Zhihai, 99.

[15] Nie Rongzhen Memoir, 744.

[16] Anatoly Torkunov, The War in Korea 1950-1953: Its Origin, Bloodshed and Conclusion (Tokyo, 2000), 50-51.

[17] David, T. C. (2015). China’s military intervention in Korea: Its origins and Objectives. Trafford Publishing, 80.

[18] Kim, 1005.

[19] Roshin’s cable to Moscow, July 2, 1950, Arkhiv Prezidenta Rossiiskoi Federatsii [Archive of the President of the Russian Federation] (hereafter APRF), Fond 45, Opis 1, Delo 331, Listy 75–7.

[20] Telegram from Stalin to Roshchin, July 5, 1950, Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Sotsial’no-Politicheskoi Istorii [Russian State Archives on Social-Political History] (hereafter RGASPI), Fond 558, Opis 11, Delo 334, Listy 79.

[21] Schnabel and Watson, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 73-79.

[22] Kim, 1012.

[23] Telegram from Stalin to Mao Zedong, October 5, 1950, cited from CEDF, Vol. 7, 909-13; A. M. Ledovsky, “Stalin, Mao Zedong and the Korean War, 1950-1953,” Mmb‘~ h lmbe—w‘~ hpqmoh~ [Modern and Contemporary History] 5 (2005): 105-6.

[24] Kim, 1019.

[25] Kim, 1019.

[26] Kim, 1021.

[27] Zhou (2015).